Sunday, August 1, 2010

DNA polymerase

Polymerase chain reaction

DNA microarray

A DNA microarray is a multiplex technology used in molecular biology. It consists of an arrayed series of thousands of microscopic spots of DNA oligonucleotides, called features, each containing picomoles (10−12 moles) of a specific DNA sequence, known as probes (or reporters). This can be a short section of a gene or other DNA element that are used to hybridize a cDNA or cRNA sample (called target) under high-stringency conditions. Probe-target hybridization is usually detected and quantified by detection of fluorophore-, silver-, or chemiluminescence-labeled targets to determine relative abundance of nucleic acid sequences in the target. Since an array can contain tens of thousands of probes, a microarray experiment can accomplish many genetic tests in parallel. Therefore arrays have dramatically accelerated many types of investigation.

In standard microarrays, the probes are attached via surface engineering to a solid surface by a covalent bond to a chemical matrix (via epoxy-silane, amino-silane, lysine, polyacrylamide or others). The solid surface can be glass or a silicon chip, in which case they are colloquially known as an Affy chip when an Affymetrix chip is used. Other microarray platforms, such as Illumina, use microscopic beads, instead of the large solid support. DNA arrays are different from other types of microarray only in that they either measure DNA or use DNA as part of its detection system.

Oligonucleotide

An oligonucleotide (from Greek prefix oligo-, "having few, having little") is a short nucleic acid polymer, typically with twenty or fewer bases. Although they can be formed by bond cleavage of longer segments, they are now more commonly synthesized by polymerizing individual nucleotide precursors. Automated synthesizers allow the synthesis of oligonucleotides up to 160 to 200 bases.

The length of the oligonucleotide is usually denoted by "mer" (from Greek meros, "part"). For example, a fragment of 25 bases would be called a 25-mer. Because oligonucleotides readily bind to their respective complementary nucleotide, they are often used as probes for detecting DNA or RNA. Examples of procedures that use oligonucleotides include DNA microarrays, Southern blots, ASO analysis, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), and the synthesis of artificial genes.

Oligonucleotides composed of DNA (oligodeoxyribonucleotides) are often used in the polymerase chain reaction, a procedure that can greatly amplify almost any small piece of DNA. There, the oligonucleotide is referred to as a primer, allowing DNA polymerase to extend the oligonucleotide and replicate the complementary strand.

Polymer

A polymer is a large molecule (macromolecule) composed of repeating structural units typically connected by covalent chemical bonds. While polymer in popular usage suggests plastic, the term actually refers to a large class of natural and synthetic materials with a wide variety of properties.

Because of the extraordinary range of properties accessible in polymeric materials, they play an essential and ubiquitous role in everyday life, ranging from familiar synthetic plastics and elastomers to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are essential for life. A simple example is polyethylene, whose repeating unit is based on ethylene (IUPAC name ethene) monomer. Most commonly, as in this example, the continuously linked backbone of a polymer used for the preparation of plastics consists mainly of carbon atoms. However, other structures do exist; for example, elements such as silicon form familiar materials such as silicones, examples being silly putty and waterproof plumbing sealant. The backbone of DNA is in fact based on a phosphodiester bond, and repeating units of polysaccharides (e.g. cellulose) are joined together by glycosidic bonds via oxygen atoms.

Complementary DNA

Gel electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is a technique used for the separation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), ribonucleic acid (RNA), or protein molecules using an electric field applied to a gel matrix. DNA Gel electrophoresis is usually performed for analytical purposes, often after amplification of DNA via PCR, but may be used as a preparative technique prior to use of other methods such as mass spectrometry, RFLP, PCR, cloning, DNA sequencing, or Southern blotting for further characterization.

Illumina Methylation Assay

Allele Specific Oligonucleotide

Denaturing gel

Northern blot

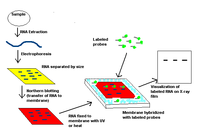

The northern blot is a technique used in molecular biology research to study gene expression by detection of RNA (or isolated mRNA) in a sample.

With northern blotting it is possible to observe cellular control over structure and function by determining the particular gene expression levels during differentiation, morphogenesis, as well as abnormal or diseased conditions. Northern blotting involves the use of electrophoresis to separate RNA samples by size, and detection with a hybridization probe complementary to part of or the entire target sequence. The term 'northern blot' actually refers specifically to the capillary transfer of RNA from the electrophoresis gel to the blotting membrane, however the entire process is commonly referred to as northern blotting. The northern blot technique was developed in 1977 by James Alwine, David Kemp, and George Stark at Stanford University.Northern blotting takes its name from its similarity to the first blotting technique, the Southern blot, named for biologist Edwin Southern. The major difference is that RNA, rather than DNA, is analyzed in the northern blot.

Genetically modified organism

Transgene

A transgene is a gene or genetic material that has been transferred naturally or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques from one organism to another.

In its most precise usage, the term transgene describes a segment of DNA containing a gene sequence that has been isolated from one organism and is introduced into a different organism. This non-native segment of DNA may retain the ability to produce RNA or protein in the transgenic organism, or it may alter the normal function of the transgenic organism's genetic code. In general, the DNA is incorporated into the organism's germ line. For example, in higher vertebrates this can be accomplished by injecting the foreign DNA into the nucleus of a fertilized ovum. This technique is routinely used to introduce human disease genes or other genes of interest into strains of laboratory mice to study the function or pathology involved with that particular gene.

In looser usage, transgene can describe any DNA sequence, regardless of whether it contains a gene coding sequence or it has been artificially constructed, which has been introduced into an organism or vector construct in which it was previously not found.