Sunday, August 1, 2010

DNA polymerase

Polymerase chain reaction

DNA microarray

A DNA microarray is a multiplex technology used in molecular biology. It consists of an arrayed series of thousands of microscopic spots of DNA oligonucleotides, called features, each containing picomoles (10−12 moles) of a specific DNA sequence, known as probes (or reporters). This can be a short section of a gene or other DNA element that are used to hybridize a cDNA or cRNA sample (called target) under high-stringency conditions. Probe-target hybridization is usually detected and quantified by detection of fluorophore-, silver-, or chemiluminescence-labeled targets to determine relative abundance of nucleic acid sequences in the target. Since an array can contain tens of thousands of probes, a microarray experiment can accomplish many genetic tests in parallel. Therefore arrays have dramatically accelerated many types of investigation.

In standard microarrays, the probes are attached via surface engineering to a solid surface by a covalent bond to a chemical matrix (via epoxy-silane, amino-silane, lysine, polyacrylamide or others). The solid surface can be glass or a silicon chip, in which case they are colloquially known as an Affy chip when an Affymetrix chip is used. Other microarray platforms, such as Illumina, use microscopic beads, instead of the large solid support. DNA arrays are different from other types of microarray only in that they either measure DNA or use DNA as part of its detection system.

Oligonucleotide

An oligonucleotide (from Greek prefix oligo-, "having few, having little") is a short nucleic acid polymer, typically with twenty or fewer bases. Although they can be formed by bond cleavage of longer segments, they are now more commonly synthesized by polymerizing individual nucleotide precursors. Automated synthesizers allow the synthesis of oligonucleotides up to 160 to 200 bases.

The length of the oligonucleotide is usually denoted by "mer" (from Greek meros, "part"). For example, a fragment of 25 bases would be called a 25-mer. Because oligonucleotides readily bind to their respective complementary nucleotide, they are often used as probes for detecting DNA or RNA. Examples of procedures that use oligonucleotides include DNA microarrays, Southern blots, ASO analysis, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), and the synthesis of artificial genes.

Oligonucleotides composed of DNA (oligodeoxyribonucleotides) are often used in the polymerase chain reaction, a procedure that can greatly amplify almost any small piece of DNA. There, the oligonucleotide is referred to as a primer, allowing DNA polymerase to extend the oligonucleotide and replicate the complementary strand.

Polymer

A polymer is a large molecule (macromolecule) composed of repeating structural units typically connected by covalent chemical bonds. While polymer in popular usage suggests plastic, the term actually refers to a large class of natural and synthetic materials with a wide variety of properties.

Because of the extraordinary range of properties accessible in polymeric materials, they play an essential and ubiquitous role in everyday life, ranging from familiar synthetic plastics and elastomers to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are essential for life. A simple example is polyethylene, whose repeating unit is based on ethylene (IUPAC name ethene) monomer. Most commonly, as in this example, the continuously linked backbone of a polymer used for the preparation of plastics consists mainly of carbon atoms. However, other structures do exist; for example, elements such as silicon form familiar materials such as silicones, examples being silly putty and waterproof plumbing sealant. The backbone of DNA is in fact based on a phosphodiester bond, and repeating units of polysaccharides (e.g. cellulose) are joined together by glycosidic bonds via oxygen atoms.

Complementary DNA

Gel electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is a technique used for the separation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), ribonucleic acid (RNA), or protein molecules using an electric field applied to a gel matrix. DNA Gel electrophoresis is usually performed for analytical purposes, often after amplification of DNA via PCR, but may be used as a preparative technique prior to use of other methods such as mass spectrometry, RFLP, PCR, cloning, DNA sequencing, or Southern blotting for further characterization.

Illumina Methylation Assay

Allele Specific Oligonucleotide

Denaturing gel

Northern blot

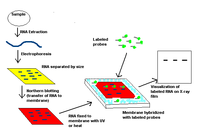

The northern blot is a technique used in molecular biology research to study gene expression by detection of RNA (or isolated mRNA) in a sample.

With northern blotting it is possible to observe cellular control over structure and function by determining the particular gene expression levels during differentiation, morphogenesis, as well as abnormal or diseased conditions. Northern blotting involves the use of electrophoresis to separate RNA samples by size, and detection with a hybridization probe complementary to part of or the entire target sequence. The term 'northern blot' actually refers specifically to the capillary transfer of RNA from the electrophoresis gel to the blotting membrane, however the entire process is commonly referred to as northern blotting. The northern blot technique was developed in 1977 by James Alwine, David Kemp, and George Stark at Stanford University.Northern blotting takes its name from its similarity to the first blotting technique, the Southern blot, named for biologist Edwin Southern. The major difference is that RNA, rather than DNA, is analyzed in the northern blot.

Genetically modified organism

Transgene

A transgene is a gene or genetic material that has been transferred naturally or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques from one organism to another.

In its most precise usage, the term transgene describes a segment of DNA containing a gene sequence that has been isolated from one organism and is introduced into a different organism. This non-native segment of DNA may retain the ability to produce RNA or protein in the transgenic organism, or it may alter the normal function of the transgenic organism's genetic code. In general, the DNA is incorporated into the organism's germ line. For example, in higher vertebrates this can be accomplished by injecting the foreign DNA into the nucleus of a fertilized ovum. This technique is routinely used to introduce human disease genes or other genes of interest into strains of laboratory mice to study the function or pathology involved with that particular gene.

In looser usage, transgene can describe any DNA sequence, regardless of whether it contains a gene coding sequence or it has been artificially constructed, which has been introduced into an organism or vector construct in which it was previously not found.

Southern blot

SDS-PAGE

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Macromolecule blotting and probing

Gel electrophoresis

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

Molecular Recognition

Metalloproteins and metalloenzymes

These are metal complexes of proteins. In many cases, the metal ion is coordinated directly to functional groups on amino acid residues. In some cases, the protein contains a bound metallo-cofactor such as heme. In metalloproteins with more than one metal-binding site, the metal ions may be found in clusters. Examples include ferredoxins, which contain iron-sulfur clusters (Fe2S2 or Fe4S4), and nitrogenase, which contains both Fe4S4 units and a novel MoFe7S8 cluster. See also Protein.

Some metalloproteins are designed for the storage and transport of the metal ions themselves—for example, ferritin and transferrin for iron and metallothionein for zinc. Others, such as the yeast protein Atx1, act as metallochaperones that aid in the insertion of the appropriate metal ion into a metalloenzyme. Still others function as transport agents. Cytochromes and ferredoxins facilitate the transfer of electrons in various metabolic processes.

Low-molecular-weight compounds

A number of coordination compounds found in organisms have relatively low molecular weights. Ionophores, molecules that are able to carry ions across lipid barriers, are polydentate ligands designed to bind alkali and alkaline-earth metal ions; they span membranes and serve to transport such ions across these biological barriers. Molecular receptors known as siderophores are also polydentate ligands; they have a very high affinity for iron. See also Ionophore.

Other low-molecular-weight compounds are metal-containing cofactors that interact with macromolecules to promote important biological processes. Perhaps the most widely studied of the metal ligands found in biochemistry are the porphyrins; iron protoporphyrin IX (see illustration) is an example of the all-important complex in biology known as heme. Chlorophyll and vitamin B12 are chemically related to the porphyrins. Magnesium is the central metal ion in chlorophyll, which is the green pigment in plants used to convert light energy into chemical energy. Cobalt is the central metal ion in vitamin B12; it is converted into coenzyme B12 in cells, where it participates in a variety of enzymatic reactions.Bioinorganic chemistry

Biochemistry

Supramolecular chemistry

A highly interdisciplinary field covering the chemical, physical, and biological features of complex chemical species held together and organized by means of intermolecular (noncovalent) bonding interactions. See also Chemical bonding; Intermolecular forces.

When a substrate binds to an enzyme or a drug to its target, and when signals propagate between cells, highly selective interactions occur between the partners that control the processes. Supramolecular chemistry is concerned with the study of the basic features of these interactions and with their implementation in biological systems as well as in specially designed nonnatural ones. In addition to biochemistry, its roots extend into organic chemistry and the synthetic procedures for receptor construction, into coordination chemistry and metal ion-ligand complexes, and into physical chemistry and the experimental and theoretical studies of interactions. See also Bioinorganic chemistry; Enzyme; Ligand field theory; Physical organic chemistry; Protein.

Saturday, April 10, 2010

Host-guest chemistry

Rotaxane

A rotaxane is a mechanically-interlocked molecular architecture consisting of a "dumbbell shaped molecule" which is threaded through a "macrocycle" (see graphical representation). The name is derived from the Latin for wheel (rota) and axle (axis). The two components of a rotaxane are kinetically trapped since the ends of the dumbbell (often called stoppers) are larger than the internal diameter of the ring and prevent disassociation (unthreading) of the components since this would require significant distortion of the covalent bonds.

Much of the research concerning rotaxanes and other mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures, such as catenanes, has been focused on their efficient synthesis. However, examples of rotaxane have been found in biological systems including: cystine knot peptides, cyclotides or lasso-peptides such as microcin J25 are protein, and a variety of peptides with rotaxane substructure.

Mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures

Mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures are connections of molecules not through traditional bonds, but instead as a consequence of their topology. This connection of molecules is analogous to keys on a key chain loop. The keys are not directly connected to the key chain loop but they cannot be separated without breaking the loop. On the molecular level the interlocked molecules cannot be separated without significant distortion of the covalent bonds that make up the conjoined molecules. Examples of mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures include catenanes, rotaxanes, molecular knots, and molecular Borromean rings.

The synthesis of such entangled architectures has been made efficient through the combination of supramolecular chemistry with traditional covalent synthesis, however mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures have properties that differ from both “supramolecular assemblies” and “covalently-bonded molecules”. Recently the terminology "mechanical bond" has been coined to describe the connection between the components of mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures. Although research into mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures is primarily focused on artificial compounds many examples have been found in biological systems including: cystine knots, cyclotides or lasso-peptides such as microcin J25 are protein, and a variety of peptides. There is a great deal of interest in mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures to develop molecular machines by manipulating the relative position of the components.

Protein subunit

In structural biology, a protein subunit or subunit protein is a single protein molecule that assembles (or "coassembles") with other protein molecules to form a protein complex: a multimeric or oligomeric protein. Many naturally-occurring proteins and enzymes are multimeric. Examples include: oligomeric: hemoglobin, DNA polymerase, nucleosomes and multimeric: ion channels, microtubules and other cytoskeleton proteins. The subunits of a multimeric protein may be identical, homologous or totally dissimilar and dedicated to disparate tasks. In some protein assemblies, one subunit may be referred to as a "regulatory subunit" and another as a "catalytic subunit." An enzyme composed of both regulatory and catalytic subunits when assembled is often referred to as a holoenzyme. One subunit is made of one polypeptide chain. A polypeptide chain has one gene coding for it – meaning that a protein must have one gene for each unique subunit.

A subunit is often named with a Greek or Roman letter, and the numbers of this type of subunit in a protein is indicated by a subscript. For example, ATP synthase has a type of subunit called α. Three of these are present in the ATP synthase molecule, and is therefore designated α3. Larger groups of subunits can also the specified, like α3β3-hexamer and c-ring.

Biochemistry

Biochemistry is the study of the chemical processes in living organisms. It deals with the structures and functions of cellular components such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids and other biomolecules.

Among the vast number of different biomolecules, many are complex and large molecules (called polymers), which are composed of similar repeating subunits (called monomers). Each class of polymeric biomolecule has a different set of subunit types. For example, a protein is a polymer whose subunits are selected from a set of 20 or more amino acids. Biochemistry studies the chemical properties of important biological molecules, like proteins, and in particular the chemistry of enzyme-catalyzed reactions.

The biochemistry of cell metabolism and the endocrine system has been extensively described. Other areas of biochemistry include the genetic code (DNA, RNA), protein synthesis, cell membrane transport, and signal transduction.

Protein nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Structural biology

Structural biology is a branch of molecular biology, biochemistry, and biophysics concerned with the molecular structure of biological macromolecules, especially proteins and nucleic acids, how they acquire the structures they have, and how alterations in their structures affect their function. This subject is of great interest to biologists because macromolecules carry out most of the functions of cells, and because it is only by coiling into specific three-dimensional shapes that they are able to perform these functions. This architecture, the "tertiary structure" of molecules, depends in a complicated way on the molecules' basic composition, or "primary structures."

Biomolecules are too small to see in detail even with the most advanced light microscopes. The methods that structural biologists use to determine their structures generally involve measurements on vast numbers of identical molecules at the same time. These methods include:

- Macromolecular crystallography,

- NMR,

- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)

- Multiangle light scattering,

- Small angle scatterng,

- Ultra fast laser spectroscopy, and

- Dual Polarisation Interferometry and circular dichroism.

X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is a method of determining the arrangement of atoms within a crystal, in which a beam of X-rays strikes a crystal and diffracts into many specific directions. From the angles and intensities of these diffracted beams, a crystallographer can produce a three-dimensional picture of the density of electrons within the crystal. From this electron density, the mean positions of the atoms in the crystal can be determined, as well as their chemical bonds, their disorder and various other information.

Since many materials can form crystals — such as salts, metals, minerals, semiconductors, as well as various inorganic, organic and biological molecules — X-ray crystallography has been fundamental in the development of many scientific fields. In its first decades of use, this method determined the size of atoms, the lengths and types of chemical bonds, and the atomic-scale differences among various materials, especially minerals and alloys. The method also revealed the structure and functioning of many biological molecules, including vitamins, drugs, proteins and nucleic acids such as DNA. X-ray crystallography is still the chief method for characterizing the atomic structure of new materials and in discerning materials that appear similar by other experiments. X-ray crystal structures can also account for unusual electronic or elastic properties of a material, shed light on chemical interactions and processes, or serve as the basis for designing pharmaceuticals against diseases.

Polymer

A polymer is a large molecule (macromolecule) composed of repeating structural units typically connected by covalent chemical bonds. While polymer in popular usage suggests plastic, the term actually refers to a large class of natural and synthetic materials with a wide variety of properties.

Because of the extraordinary range of properties accessible in polymeric materials, they play an essential and ubiquitous role in everyday life—from plastics and elastomers on the one hand to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are essential for life on the other. A simple example is polyethylene, whose repeating unit is based on ethylene (IUPAC name ethene) monomer. Most commonly, as in this example, the continuously linked backbone of a polymer used for the preparation of plastics consists mainly of carbon atoms. However, other structures do exist; for example, elements such as silicon form familiar materials such as silicones, examples being silly putty and waterproof plumbing sealant. The backbone of DNA is in fact based on a phosphodiester bond, and repeating units of polysaccharides (e.g. cellulose) are joined together by glycosidic bonds via oxygen atoms.

Sulfur

Oxygen

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element that has the symbol N, atomic number of 7 and atomic mass 14.00674 u. Elemental nitrogen is a colorless, odorless, tasteless and mostly inert diatomic gas at standard conditions, constituting 78% by volume of Earth's atmosphere.

Many industrially important compounds, such as ammonia, nitric acid, organic nitrates (propellants and explosives), and cyanides, contain nitrogen. The extremely strong bond in elemental nitrogen dominates nitrogen chemistry, causing difficulty for both organisms and industry in breaking the bond to convert the N2 into useful compounds, but releasing large amounts of often useful energy, when these compounds burn, explode, or decay back into nitrogen gas.

The element nitrogen was discovered by Scottish physician Daniel Rutherford in 1772. Nitrogen occurs in all living organisms. It is a constituent element of amino acids and thus of proteins, and of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). It resides in the chemical structure of almost all neurotransmitters, and is a defining component of alkaloids, biological molecules produced by many organisms.

Hydrogen

Carbon

Carbon is the chemical element with symbol C and atomic number 6. As a member of group 14 on the periodic table, it is nonmetallic and tetravalent—making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. There are three naturally occurring isotopes, with 12C and 13C being stable, while 14C is radioactive, decaying with a half-life of about 5730 years. Carbon is one of the few elements known since antiquity. The name "carbon" comes from Latin language carbo, coal.

There are several allotropes of carbon of which the best known are graphite, diamond, and amorphous carbon. The physical properties of carbon vary widely with the allotropic form. For example, diamond is highly transparent, while graphite is opaque and black. Diamond is among the hardest materials known, while graphite is soft enough to form a streak on paper (hence its name, from the Greek word "to write"). Diamond has a very low electrical conductivity, while graphite is a very good conductor. Under normal conditions, diamond has the highest thermal conductivity of all known materials. All the allotropic forms are solids under normal conditions but graphite is the most thermodynamically stable.

Protein structure

Molecule

A molecule is defined as an electrically neutral group of at least two atoms in a definite arrangement held together by very strong (covalent) chemical bonds. Molecules are distinguished from polyatomic ions in this strict sense. In organic chemistry and biochemistry, the term molecule is used less strictly and also is applied to charged organic molecules and biomolecules.

In the kinetic theory of gases, the term molecule is often used for any gaseous particle regardless of its composition. According to this definition noble gas atoms are considered molecules despite the fact that they are composed of a single non-bonded atom.

A molecule may consist of atoms of a single chemical element, as with oxygen (O2), or of different elements, as with water (H2O). Atoms and complexes connected by non-covalent bonds such as hydrogen bonds or ionic bonds are generally not considered single molecules.

Dynamic covalent chemistry

In supramolecular chemistry, dynamic covalent chemistry is a strategy that aims at synthesizing large complex molecules. In it a reversible reaction is under thermodynamic reaction control and a specific reaction product out of many is captured . Because all the components in the reaction mixture are able to equilibrate quickly, (according to its advocates) some degree of error checking and proof reading is enabled. The concept of dynamic covalent chemistry was demonstrated in the development of specific molecular Borromean rings.

The underlying idea is that rapid equilibration allows the coexistence of a huge variety of different species among which one can select molecules with desired chemical, pharmaceutical and biological properties. For instance, the addition of a proper template will shift the equilibrium toward the component that forms the complex of higher stability (thermodynamic template effect). After the new equilibrium is established, the researcher modifies the reaction conditions so as to stop equilibration. The optimal binder for the template is then extracted from the reactional mixture by the usual laboratory procedures.